Halloween Prelude, 4th Edition.

Halloween creeps closer, and with it, the opening of Macabre & Mysticism at Red Roots Gallery on Saturday, October 29th. Conveyor Editor Dominica Paige continues her foray into the the unnerving (and sometimes terrifying) realms of photography.

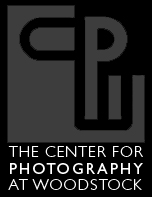

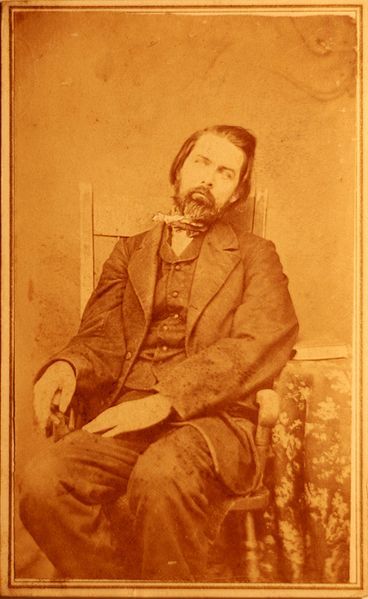

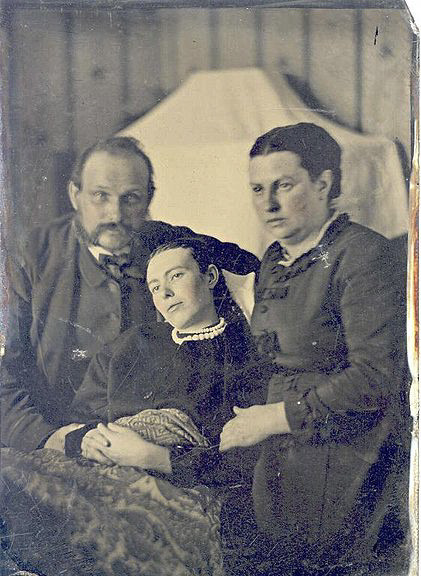

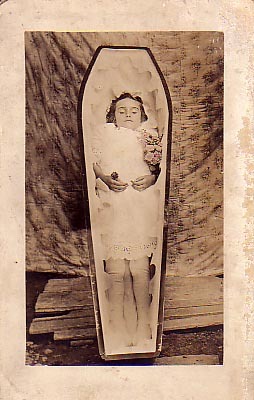

Memento Mori & Victorian Portraiture of the Deceased.

Postmortem photography, which seems rather morose and morbid in modern life, was quite widespread in Europe and the United States during the 19th century.

With the invention of the daguerreotype, portraiture became widespread amongst the middle class who could afford a session with a photographer but were unable to commission a painted portrait. This less expensive and more convenient form of portraiture was also used as a means for memorializing dead loved ones.

Unlike traditional memento mori, these photos served less as a admonition of mortality and function rather as a keepsake to remember the deceased. Memorializing the dead was particularly common with children and infants, as childhood mortality was common during the Victorian era, and in many cases, a postmortem photograph might be the only image ever made of a child. Children were often depicted with family members or a favorite plaything, or in recline in a crib.

The living appearance was so desirable that, later in history, the photograph would depict the subject with their eyes propped open, pupils often painted onto the photo; the image, especially tintypes and ambrotypes, was commonly manipulated to make the deceased’s face rosy.

This is terrifying.

Later efforts were less concerned with a lifelike quality and the deceased were shown in coffin, and some very late examples show the dead accompanied by a large group of funeral attendees.

Halloween Prelude, Episode Three.

In which our faithful narrator, Conveyor Editor Dominica Paige continues her week-long spooktacular of unnerving photography. Read on…if you dare! (mwah-hahahahaaa!)

What’s spookier than a fire creeping underground that burns for decades, causing human-swallowing sink holes and the abandonment of an entire town? Perhaps the most infamous instance of a ghost town is Centralia, PA, where a mine fire began in 1962 and continues to burn; in fact, it is estimated that there is enough coal in the mine to sustain the fire for the next 250 years.

Matt McDonough

In 1981, there were over 1,000 residents in Centralia; in 2010, there were 10. In 2002, the town’s zip code was revoked by USPS. Matt McDonough’s series-in-progress entitled Centralia examines the nearly-deserted town.

Matt McDonough

Matt McDonough

{ http://mattmcdphoto.com }

26 Oct 2011 / 1 note / centralia Matt McDonough Halloween Dominica Paige

Halloween Prelude, Part Deux.

The countdown continues: six days until Halloween, and four days until the opening of Macabre & Mysticism at Red Roots Gallery. In the spirit of the season, Conveyor Editor Dominica Paige is posting daily featuring the creepier side of photography.

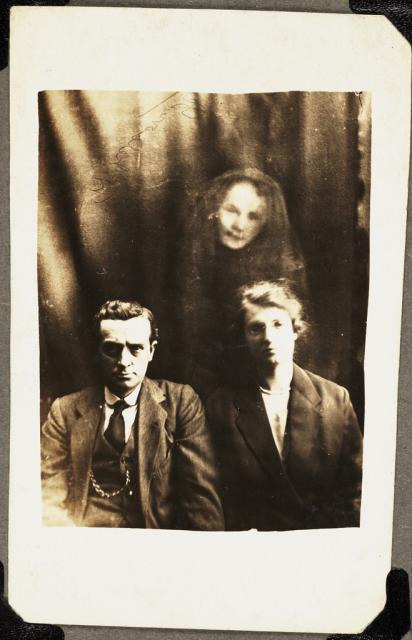

The Spirit Photography of William Hope

William Hope, Woman with Two Boys and a Female Spirit, Collection of National Media Museum

William Hope’s aptitude for capturing spirits in photographs allegedly came about in 1905 when he and a friend were photographing one another. In one of the photos taken by Hope, another entity appeared in the image, an “extra,” the image of a person who was not physically present when the photo was taken. The extra in question was the deceased sister of Hope’s friend.

William Hope, Will Thomas with an Unidentified Spirit, Collection of the National Media Museum

Typically in the photographs, ghostly faces appear, floating above or behind the living subjects. In some images, fully formed ghosts would appear, usually draped in sheets. Superimposed images and double exposures were the usual methods for “capturing” the ghosts, though the photographer’s assistant could also drift behind the sitter, dressed in appropriate “spirit” attire, and remain in place a few moments while the shutter was open before ducking out of site.

William Hope, Couple with a Female Spirit, Collection of the National Media Museum

Hope became a prominent spirit photographer and formed the Crewe Spiritualists Circle with six other photographers. During their early work, the circle destroyed the negatives of the photos they created as they feared being suspected of witchcraft. They began to make their work public, however, when Archbishop Thomas Colley, a lifelong enthusiast of both the supernatural and Spiritualism, joined the circle.

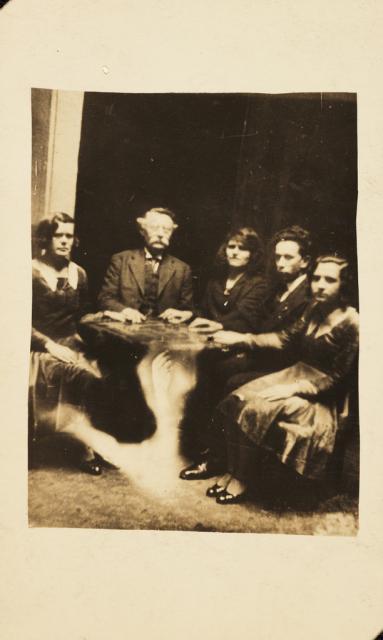

William Hope, A Seance, ca. 1920, Collection of the National Media Museum

In 1922 Hope relocated to London and became a professional medium. The work of the Crewe Circle was investigated on various occasions by paranormal investigators who hoped to prove Hope was a charlatan.The most famous of these took place in 1922, when the Society for Psychical Research sent Harry Price to investigate for fraud. Price collected evidence that Hope was substituting glass plates bearing ghostly images in order to produce his spirit photographs; he provided Hope with glass plates embossed with a special mark that could not be seen except when exposed. Hope substituted these for regular glass plates, and as such the marks did not show up – suggesting that he faked his photographs.

William Hope, Mourning Scene, ca. 1920, Collection of the National Media Museum

Still, hundreds of followers continued to believe Hope’s abilities were genuine. This remains a matter for conjecture, a mystery that remains unsolved. What can be said with certainty is he was rather adept at capturing photographic ghosts, whether real or imagined.

25 Oct 2011 / 3 notes / William Hope Spirit Photography Halloween Dominica Paige